How to watch Baseball: Pay attention to the count

It will make Opening Day way more interesting...

Today is Opening Day and I really don’t see why Columbus Day is a National Holiday (apparently Christopher was a Big Ass racist with a poor sense of direction) and Opening Day isn’t a national Holiday so if you’re in Congress and read this, I’d really appreciate it if you got right on that.

Moving on.

On a semi-regular basis I say you have to pay attention if you want Baseball to be interesting and today seems like a pretty good day to write about what you should pay attention to.

Heads up; if you want to understand baseball, this is important

The first thing you need to know is the easiest pitch to throw for a strike is a fastball because it’s relatively straight.

The second thing you need to know is the easiest pitch to hit is also a fastball because it’s relatively straight.

Once you get your mind around those two facts, Baseball becomes a lot easier to comprehend and you’ll not only understand what just happened, but you’ll be able to make a pretty good guess about what’s going to happen next.

There are 1,001 exceptions, but generally speaking hitters want to hit fastballs and they’ll look for one when the pitcher falls behind in the count, needs to throw a strike and the most likely pitch is that relatively straight fastball.

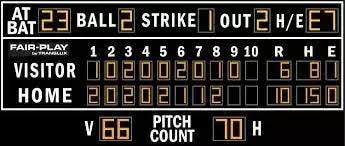

2-0, 2-1, 3-0, 3-1 and (depending on the situation) 3-2 are usually considered “fastball counts” so a pitcher wants to stay out of those counts because baseballs tend to get hit really, really hard when pitchers throw a fastball the hitter is expecting.

For example: in 2021, the worst-hitting team in the Big Leagues was the Seattle Mariners. Their team average was .226, but put the Mariners in a 2-0 fastball count and they hit .385.

In a count where they had a pretty good idea what was coming, the Mariners hit like Hall of Famers, which is why the Houston Astros wanted to tip the odds in their favor by cheating.

Hall of Famer Mike Schmidt once said every at-bat contained a hittable fastball and it was his job to find it. So that’s what’s at the heart of many baseball situations: hitters trying to find a hittable fastball and pitchers trying to avoid throwing one when the hitter expects it.

Pitch identification during warmups

Before an inning starts, a pitcher gets 8 warm-up pitches and the catcher needs to know what’s coming so the pitcher will signal that with his glove:

If he flips his glove toward the catcher with the palm down, that’s a fastball.

If he flips his glove toward the catcher with the palm up, that’s a curveball.

If he makes a sideways motion with his glove, that’s a slider.

If he points his glove at the catcher and then pulls it back toward himself, that’s a changeup.

Bonus information: just in case the catcher lost count, before the pitcher throws his last warm-up pitch the pitcher will point back over his shoulder, which reminds the catcher to throw the ball to second base after the next pitch. The catcher will then hold a glove or hand out to the side to remind a middle infielder to cover second base and the middle infielder that’s taking the throw will hold his glove or hand out to the side to let that catcher know, “Yeah, I saw you” and they do all that so they don’t look like idiots when the catcher fires a throw to second base and nobody’s there.

Pay attention to the pitcher’s glove during warm-ups and he’ll show you what pitches he throws and he may also show you what pitch he’s having trouble with because if he throws five sliders he might be trying to get a feel for it.

If the pitcher throws less than 8 pitches that might be an intimidation move – “I don’t need 8 warm-up pitches to handle you guys” – or it might be because his arm is killing him and he doesn’t want to throw any more pitches than necessary.

(See? Once you know what to watch, even warm-ups are interesting.)

Pitch identification during the game

If you watch a bazillion pitches after a while you can spot fastballs (they stay relatively straight all the way to the catcher’s mitt) and off-speed pitches (they start to drop before reaching the catcher’s mitt), but just in case you don’t have time to watch a bazillion pitches because you have an actual Life, you can just read pitch velocity.

If you’re watching on TV it will show up on the on-screen graphic and in a ballpark it will be somewhere on a scoreboard unless the manager got sick and tired of his pitchers throwing a pitch, then turning around to see just how hard they threw it so the manager got pissed off and told them to stop putting velocity readings on the scoreboard. (A series of events that actually happened in real life…hint: the team was not the Royals.)

Generally speaking (and I’m going to keep saying that because of those 1,001 exceptions I mentioned earlier) any pitch over 90-MPH will be a fastball and any pitch under 90-MPH will be off-speed and if you want to know how to tell the difference between a slider and a cutter, they’re so similar you got absolutely no chance, so just try to identify fastballs and off-speed pitches and leave it at that.

Also: if a pitcher has a fastball and a slider he throws harder than 90-MPH he’s a Badass with a capital “B.”

The “ambush”

Strictly speaking the first pitch of an at-bat is not a fastball count, but the fastball is still a popular first pitch because pitchers want to throw a strike and get ahead in the count and to show why they do this we’ll use your hometown Kansas City Royals.

In 2021 if the Royals took the first pitch for a ball, after that they hit .259; if they took the first pitch for a strike after that they hit .211.

Think of it this way: if a pitcher throws a first-pitch strike, he can try to hit half-a-microbe on a corner of the plate for the next two, maybe three, pitches.

But if the pitcher throws the first pitch for a ball, he needs to get back in the strike zone right away because he doesn’t want to go 2-0 so he needs to throw more toward the middle of the plate because he has to throw a strike and can’t afford to nibble at a corner and miss it.

And now, just to make things more complicated, here’s one of those exceptions:

Let’s say the guy at the plate is hotter than Rosario Dawson in the Sahara Desert (and for you ladies or guys who swing that way, let’s make it Brad Pitt) and the pitcher would rather walk the hot hitter than give him a hittable fastball and I’ve seen pitchers walk a hitter with the bases loaded because if you’ve got a 3-run lead, walking in a run is better than giving up a Grand Slam.

If a pitcher says he wouldn’t “give in” it means he wouldn’t throw a fastball toward the middle of the plate and just kept trying to hit a corner or throwing off-speed pitches.

Knowing pitchers want to get ahead in the count, some hitters will “ambush” a first-pitch fastball and just in case you’ve forgotten, that’s what Alcides Escobar was doing in 2015; that season Esky hit .257 overall, but if he put the first pitch in play Esky hit .364.

Alcides was also hitting .364 in the first 13 games of the 2015 postseason – right up until the Mets Noah Syndergaard said “enough of this ambush crap” and threw the first pitch of Game 3 at Esky’s head.

After that knockdown pitch, Esky hit .200 which is why pitchers like Don Drysdale used to knock down hitters on a regular basis because it’s hard to duck and swing a bat at the same time, but now Baseball is kinder and gentler and a lot less interesting.

The importance of off-speed pitches in fastball counts

Generally speaking (we’re back to that again) top-of-the-line pitchers can throw their off-speed stuff for strikes and that means hitters aren’t 100 percent sure what’s coming in fastball counts.

Lesser pitchers have no idea where their curveball is going so they have to give hitters fastballs when hitters expect fastballs and if you want to get away with that, you better have a really great fastball or be able to put a fastball in a hard-to-hit location.

Or…

You could “pitch to contact” which means letting the hitter put the ball in play, but putting some movement on the pitch so the hitter doesn’t hit it squarely off the barrel of the bat and that’s way more efficient and entertaining to watch and games go faster because the pitcher is saying “Here’s that fastball you wanted, but it’s got a little dip at the end” which is what Greg Maddux was doing the day he threw a complete game with just 77 pitches. But analytics screwed that up and now pitchers try to strike everybody out all the time no matter the situation because these days, that’s what gets you paid.

The Get-Me-Over breaking pitch

In order to throw curves and sliders for strikes, some pitchers take something off the pitch and because it breaks less it’s easier to control and even though it’s a mediocre curve or slider (AKA: “A Get-Me-Over Breaking Pitch”) a hitter who’s looking for a fastball (AKA: “Sitting Dead Red”) will take the pitch for a strike which is why you see hitters take pitches that look hittable — they were looking for a different pitch.

But a pitcher better know the hitter has a game plan and is hunting fastballs, because the same Get-Me-Over Curve that a veteran might take because it’s not what he’s looking for, can get hit 400 feet by a rookie because the rookie’s got no game plan at all and swings at anything in the same zip code.

Two-strike counts

If the pitcher is ahead 0-1, 0-2, 1-2, or 2-2 – depending on how you think about it because he’s got another pitch to work with until he absolutely has to throw a strike – all his pitches remain in play and that means a hitter can’t be picky and has to try to hit fastballs, sliders, curves, cutters, sinkers, change ups, knuckleballs (assuming anyone still throws one of those) and the kitchen sink if a pitcher manages to drag one to the mound and chucks it in the direction of home plate and I’m assuming the Houston Astros are working on this if they can just find a qualified plumber with low morals.

And to show how much harder it is to hit everything as opposed to waiting for a fastball, once they got to two strikes the Seattle Mariners hit .161.

In the old days when a hitter got two strikes on him he’d change his approach and maybe choke up and try to hit the ball the other way (right field for righties, left field for lefties) because that meant they could wait longer to swing and maybe identify pitches that started in the zone, but wouldn’t wind up there.

With two strikes the hitter’s goal should go from hitting the ball hard to just getting the ball in play, but once again analytics has changed Baseball and now a lot of guys are still trying to hit one of the home runs that will get them paid, so you see them take hittable pitches for strike 3 because it wasn’t the pitch they were looking for.

Bottom line: a hitter with two strikes should be more aggressive about swinging the bat because he can’t afford to take a borderline pitch, and as long as the count’s not 3-2 the pitcher can be less aggressive about throwing a strike because he’s got a pitch to work with.

OK, there’s way more stuff I could talk about, but you’ve got enough to think about already and one of the great things about baseball is once you start learning how to watch it, the learning never ends because there’s always something else worth knowing.

Enjoy Opening Day.

Pitcher’s warm up pitches…that was So Cool!

Thank you SO much for your continuing education on baseball. I’m learning so much and I love the way you teach. I’ve always been a fan of “small ball” and I appreciate your love and understanding of the game.