The First Rule of Hitting

An essay about pitch selection which might sound boring so I added off-color jokes...

The last man to ever hit .400 in the Big Leagues thought the first rule of hitting was getting a good pitch to hit. Hall of Famer Ted Williams once said the best hitter in baseball can’t hit a bad ball good, but I’m pretty sure he said that before Vladimir Guerrero got a hit off a bounced pitch and if you don’t believe me, here’s a video:

https://www.google.com/search?q=did+vladimir+guerrero+get+a+hit+on+a+bounced+pitch

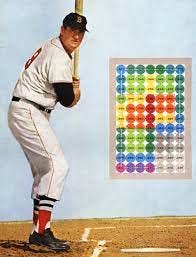

OK, so maybe Vladimir Guerrero can get away with it, but for most hitters the most important thing they can do is a get a good pitch to hit. Here’s a picture of the famous hitting chart that appeared in his book The Science of Hitting and it shows what Ted Williams hit on pitches in different locations:

The red balls are where Ted could hit .400 or more and the orange balls are where Ted could hit .390 to .400 and as you might have noticed, all those high-average balls are in the middle of the plate. (And right here there’s a joke about avoiding Blue Balls available that will make guys laugh and women think we’re even bigger idiots than they’ve always suspected we were, so maybe we should just move on.)

Anyway…

It doesn’t mean Ted couldn’t get a hit on a pitch at the edge of the strike zone, but it does mean his odds of getting a hit on those pitches went way down.

OK, so that’s our starting point: if you want to hit well, getting a good pitch to hit is the first and maybe most important step. There’s a theory worth hearing that good hitters don’t necessarily have better swings or superior eyesight or eat their Wheaties every morning; good hitters are good not because of how they swing, but because of what they swing at.

(BTW: There are a lot of exceptions to everything I’m about to say, although everything I’m about to say is generally true.)

The Kansas City Royals offense

A lot of players don’t like to talk about hitting mechanics because they don’t want to start thinking too much about an act that has to take place spontaneously and they also figure most reporters don’t really give a shit if they’re a “rotation” hitter or a “weight-shift” hitter or a “bottom-hand” guy or a “top-hand” guy or focus on “throwing the knob” or “throwing the barrel” and for the most part, players are right:

Generally speaking, most reporters don’t give a shit.

Hitting mechanics can get really complicated so reporters tend to focus on results and emotions: “You hit a home run, how did that feel?” or “The offense seems to be struggling, how do you get your confidence back?”

And since nobody really wants to get into the complicated stuff, ballplayers are happy to tell us it feels really great to hit a home run and if you’re scuffling all you can do is show up and give it your best each and every day and the Good Lord willin’ and the creek don’t rise, things will turn around soon.

As of right now this moment the Kansas City Royals have the worst team batting average in the Major Leagues and when players get asked about a team’s struggles at the plate they tend to say something extremely vague and here’s a Top-of-the Line example from Bobby Witt Jr.:

“You never want to start like this. So you’ve just got to keep learning and improving and keep getting better. I think that’s what we’ll do as a whole. Just keep moving forward.”

Right about here you might wonder: Learn what? Improve how? Move forward in what direction?

There’s a whole bunch of stuff that affects hitting like swing mechanics and launch angles and exit velocities and what ballpark you play half your games in, but today we’re going to concentrate on just one of those things and it’s something you can watch for at home which will help you understand why a hitter fails or succeeds in an at-bat.

And that’s pitch selection.

Game plans = consistency

The best hitters tend to have a game plan and early in a plate appearance they lay off pitches they aren’t looking for. Hall of Famer Mike Schmidt believed every at-bat included a hittable fastball and his job was to find it. By refusing to swing at anything else (when he was sticking to his plan) Schmidt didn’t screw up his timing when he found his hittable fastball.

Pitchers are dicks (can you tell I never pitched?) and want hitters to swing at everything; fast, slow, in, out, up down, moving and straight.

But a hitter who swings at everything can mess up his timing and you sometimes see a hitter get a hittable fastball and swing through it, foul it off or even worse – take it – and generally speaking you can’t afford to miss hittable fastball opportunities. In the Big Leagues, you don’t get that many of them.

Jason Kendall – fifth-most hits for a catcher in baseball history – believed in looking for a pitch right down the middle and didn’t care if it was a fastball or off-speed; when he got that right-down-the-middle pitch he’d take the same swing and the fastballs would go to the opposite field and the off-speed stuff would get pulled.

Hall of Famer Tony Gwynn wanted a pitch on the outer half of the plate and wrote two books saying so. Tony believed pitchers weren’t perfect and even though they knew what he was looking for, sooner or later they’d make a mistake and he’d get his pitch and that game plan worked for Gwynn 3,141 times.

The point being, whether they did it by pitch or location, all those guys had a game plan and pitches they’d swing at and pitches they’d take.

If you see a hitter swing at a slider away and then a fastball up and then a changeup down, odds are he doesn’t have much of a game plan – or if he does, he isn’t sticking to it – he’s just hacking at whatever he thinks he can reach and unless he’s Vladimir Guerrero, that probably isn’t going to work out so hot.

A look at some hitting situations

So hitters need to swing at the right pitches and here are some situations you can look for and what the pitcher will probably try to do and what the hitter probably should do.

First pitch:

Pitchers want to get ahead in the count so in a lot of at-bats the first pitch is closer to the middle of the plate which is why hitters who swing at first pitches tend to hit for a higher average than normal. But a hitter can’t do that all the time because everybody will pick up the pattern and the hitter will quit getting fat first pitches.

And if a hitter or a team gets a reputation for being overanxious and showing a willingness to chase marginal pitches, smart pitchers will throw borderline first-pitch pitches because they know the hitter will chase them.

Which is a huge mistake by the hitter, because hitters shouldn’t be chasing marginal pitches until they have to.

BTW: Don’t confuse this with “Chase Rate” which is how often a hitter chases a pitch completely out of the strike zone which the analytics guys think is a great metric, but isn’t nearly as great as they think because there are plenty of pitches in the strike zone a good hitter shouldn’t swing at.

Runner on second, no outs:

If one run matters, Old School Baseball says the hitter needs to put a groundball in play on the right side of the field. Groundballs let the runner take off right away; line drives and fly balls force the runner to wait and see if they’re caught.

Even if the hitter makes an out, a groundball to the right side allows the runner to advance to third and be there with one out which will allow that runner to score even if the next batter makes an out…as long as it’s the right kind of out.

That being the case, the pitcher wants the hitter to put the ball in play on the left side of the field and if the pitcher follows the Old School Baseball Handbook he’ll throw pitches that force right-handed hitters to pull and lefties to go the other way.

Watch and see if the hitter swings at an appropriate pitch or lets the pitcher con him into swinging at the wrong one.

Be aware that teams want some hitters to drive in that runner from second base all by themselves – forget a weak grounder to the right side – and right here Salvador Perez comes to mind.

Runner on third, less than two outs:

Depends on the defense; if they’re playing back up the middle a groundball up the middle will do the trick, but most of the time the hitter wants a ball up in the zone so he can hit a fly ball to the outfield. But pitchers know what hitters want, so they might throw a fastball “higher than high” – above the good hitting zone – and hope the hitter will chase it and swing through it or pop it up.

RBIs get hitters paid and pitchers know this so they try to tempt over-eager hitters into swinging at marginal pitches and so far this season the Royals have fallen for this way more often than they should, which helps explain a poor batting average with runners in scoring position.

Also, pitcher get paid for preventing those runs, so with a runner in scoring position pitchers might be more likely to throw their nastiest breaking pitch. Pitchers don’t throw their nastiest breaking pitch all the time because nasty breaking pitches tend to be hard on the elbow.

But don’t be surprised if a pitcher starts throwing more breaking pitches once he has a runner on second or third and don’t be surprised if a hitter who wants that RBI too much chases them.

Double play in order:

The pitcher wants a groundball so he’ll throw stuff down in the zone and the hitter wants to avoid a groundball so he wants a pitch that’s up.

Two strikes:

I once walked around spring training and asked hitters what adjustments they made once they got into a two-strike count and appalling number of them (and just so you know, I would have found any number other than zero appalling) said they made no adjustment at all and just kept doing the stuff that got them into a two-strike count to begin with.

Which might be OK if you’re a home run hitter who’s getting paid to hit 30 bombs in 600 plate appearances, but is a poor approach if you’re a singles hitter trying to stay in the Big Leagues.

Back when strikeouts still seemed to matter, a hitter with two strikes might choke up or move closer to the plate or try to hit the ball to the opposite field (which allows them to wait longer and get fooled less often) or, at the very least expand their strike zone and not let a borderline pitch go by.

But these days way too many hitters just keep trying to pull the ball because that’s how you hit one of those home runs that will get you paid. All of which helps explain why for the past five years straight there have been more strikeouts than hits which had never happened before Brad Pitt fucked up baseball.

P.S.: At the end of the 2017 season a Royals front office executive said they needed to get back to putting the ball in play because so many teams were willing to play bad defenders as long as those bad defenders hit enough home runs. But as of the moment I wrote this, only one team in the Big Leagues has struck out more often than the Royals so they’re not doing what that front office guy thought they should.

And now a word of warning

Sitting at home on your couch all this looks pretty easy: just swing at the pitches down the middle and ignore everything else until you have two strikes.

That point of view is why ballplayers say the game gets a lot easier when you’re not standing on dirt. I’ve had former Big League ballplayers say it looks so easy when they watch a game on TV and have to remind themselves it’s way harder than it looks when you’re actually standing in the batter’s box.

And good pitchers work really hard at making all their pitches look the same and pitches that appear to be right down the middle might wind up off the plate or on a corner or below the knees or neck high.

OK, that’s it for today and the point of all this is to make baseball more entertaining and baseball gets a lot more entertaining when you know what to look for.

Now go look for it.

Nice analysis, Judge! (Why does analysis start with anal?) I suspect you may have lost some readers who aren't true baseball aficionados, but I stayed with you. Why aren't you managing somewhere?!? BTW, my little brother and I are going to see the Dodgers and Phillies next month at Chavez Ravine in another bucket list checkoff.